John Muir in Yosemite, circa 1895, where he found rapture. University of the Pacific

John Muir and race: Biographer argues for nuanced view of the environmentalist

John Muir is an almost prophetlike figure in California. The 19th-century Scottish-American found rapture in the Sierra Nevada, publishing works that helped inspire the preservation of wild areas, including the designation of Yosemite as a national park in 1890.

No fewer than 70 schools, lodges, roads, and other places in California bear Muir’s name.

So it came as a jolt to many last week when the Sierra Club, of which Muir was the first president, issued a statement denouncing the environmentalist for drawing on racist stereotypes in his writings. The post, titled “Pulling down our monuments,” linked to an Atlas Obscura article that recounted how Muir had described Native Americans as “lazy” and “savages.” While walking through the South, Muir recalled encountering a “black lump of something” that turned out to be a small boy. “Birds make nests and nearly all beasts make some kind of bed for their young, but these negroes allow their younglings to lie nestless and naked in the dirt,” he wrote.

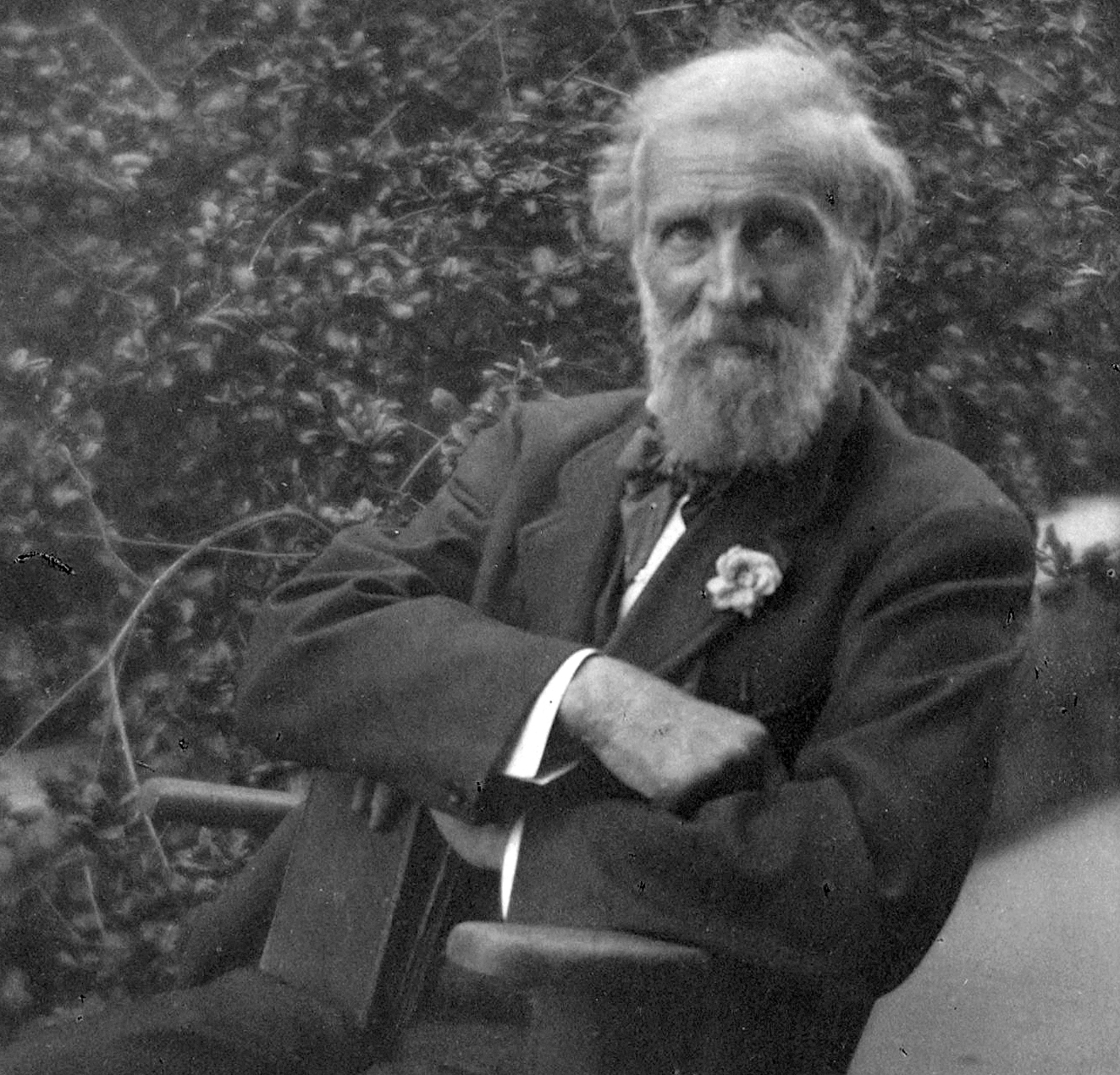

Muir at home in Martinez, circa 1890.

University of the Pacific

In an essay responding to the Sierra Club’s post, the Muir biographer Donald E. Worster acknowledged there was much to regret about Muir’s views, but argued that the environmentalist should be judged in a broader context.

“Muir has been dead for more than a century,” Worster wrote, “but if he could speak from the grave, I can easily imagine him agreeing that systemic racism is bad and should be repudiated, for he never published a word in support of black slavery, racial segregation, the Confederacy, forced sterilization of minorities, or genocidal policies toward Native Americans.”

California Sun contributor Finn Cohen reached out to ask a few questions of Worster, who is a professor emeritus of history at the University of Kansas and the author of “A Passion for Nature: The Life of John Muir.”

Excerpts of their conversation, below, have been edited and condensed for clarity.

Q. What are your feelings about the Sierra Club’s statement regarding John Muir?

A. If they just turn the page, sometimes they find some rather surprising context. Particularly that one episode from John Muir’s journal from 1868 when he was for the first time in the Yosemite area and encountered Indians coming over the mountains from Mono Lake. That gets quoted again and again. But the rest of that day’s journal entry, just something he wrote by the campfire, is quite different in tone from what most people gather from a couple of words and characterizations.

When you ignore the context, then you are cherry-picking. You’re looking for items that fit your definition. I think the Sierra Club definitely ought to be aware of who joined it over the years. A lot of people joined the club who didn’t even live in California, never came to a meeting. I think during the first several decades, the Sierra Club was probably a hiking club of very elite people who were probably full of racists and white supremacists. Of course, everybody believes the Sierra Club ought to be on today’s good side of moral values and changing social attitudes. But I fear that the way this current executive director has done this is not conducive to really rational analysis of where it’s been, or really even of its traditions or its heritage of ideas, because it is undoubtedly a lot more complex. Historians always say history is more complicated. [laughs]

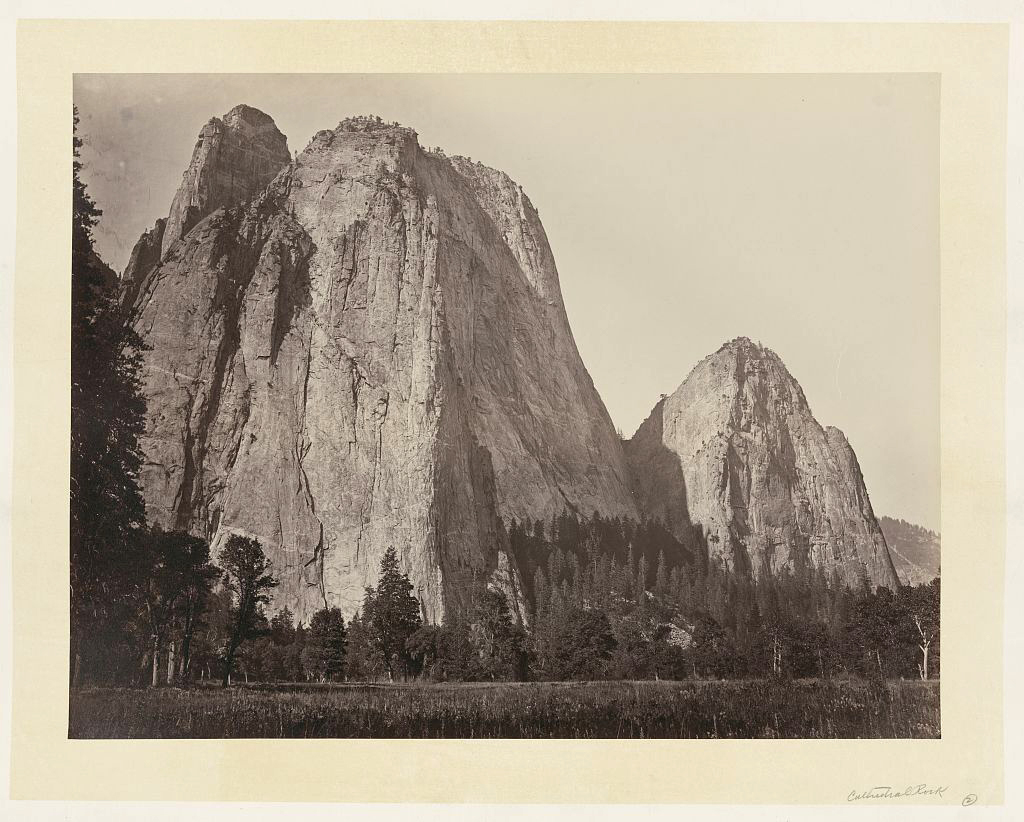

Cathedral Rocks in Yosemite, circa 1856.

Carleton Watkins

You’ve written that you found certain elements of Muir’s character that you didn’t like. Did those have anything to do with racism or xenophobia?

Xenophobia, I don’t find in John Muir. Some of his statements were probably a little insensitive or unkind, but they were written usually in a journal, and they were mostly about people he runs into. When he ran into Indians on the trail in Yosemite who were demanding cigarettes, tobacco, alcohol — John Muir was a fastidious kind of guy. He was not much of a drinker at that point in his life, so all those things repelled him. He had a lot of caustic things to say about a lot of people. He was not an easy person to get along with. I’m not sure I would have liked to go on a hike with him! [laughs] He was the kind of person who could easily offend people by his comments. But the other side of it is, this is maybe a huge paradox — he was a much-beloved man. So many people made friends with him over his lifetime and he continued those friendships.

There’s always a question of what is a racist. And this word is very loosely applied anymore. Believing in the inborn biological superiority of your group of people over others is, I think, the more classic definition of the term. I don’t find that in Muir. I find quite the opposite. There’s a scrap of paper I found when I was going through his papers, doing my research. It was jotted down when he was off the coast of China. The Chinese never get into these discussions; it’s always about Blacks or Indians. Muir lived in a state with a growing Chinese population of immigrants, and that was extremely controversial. He hired Chinese workers on his fruit farm. And when he was traveling on the coast of China, he wrote on a little scrap of paper: “Some of the best people in the world are Chinese and we must not hate them. Hatred of any race of human beings is both foolish and wicked. We should not try to flock together too closely with the Chinese, for they are birds with feathers so unlike our own they seem to have been hatched on some other planet.”

John Muir was a complicated guy. When he says, “We shouldn’t hate anybody,” he’s writing this to himself. He’s not publishing it. But I think we should take that just as seriously as we take some of the more negative things he said. It’s not always clear when he said negative things that he was opposed to people as such, or he thought that they were inferior, but maybe that culturally it was going to be hard to assimilate or amalgamate or create social bonds.

If you put that with the other comments, to call him a racist or white supremacist and just leave it at that, I think that’s really unfair. I’m saying that about the executive director of the Sierra Club, if he buys that sort of thinking. Has he really read this journal entry? Has he really tried to put all this together in his mind? Do the people who come to him and say, “I read that Muir said these Indians were dirty, and it really hurts me” — has he asked them to sit down and read the rest of the passage? We all make snap decisions, sometimes on the basis of reading a few words, but I think the job of the Sierra Club ought to be to help people think about the past and its complexities, the gray tones, and use this to educate their own members, educate the public about what an environmental movement should look like.

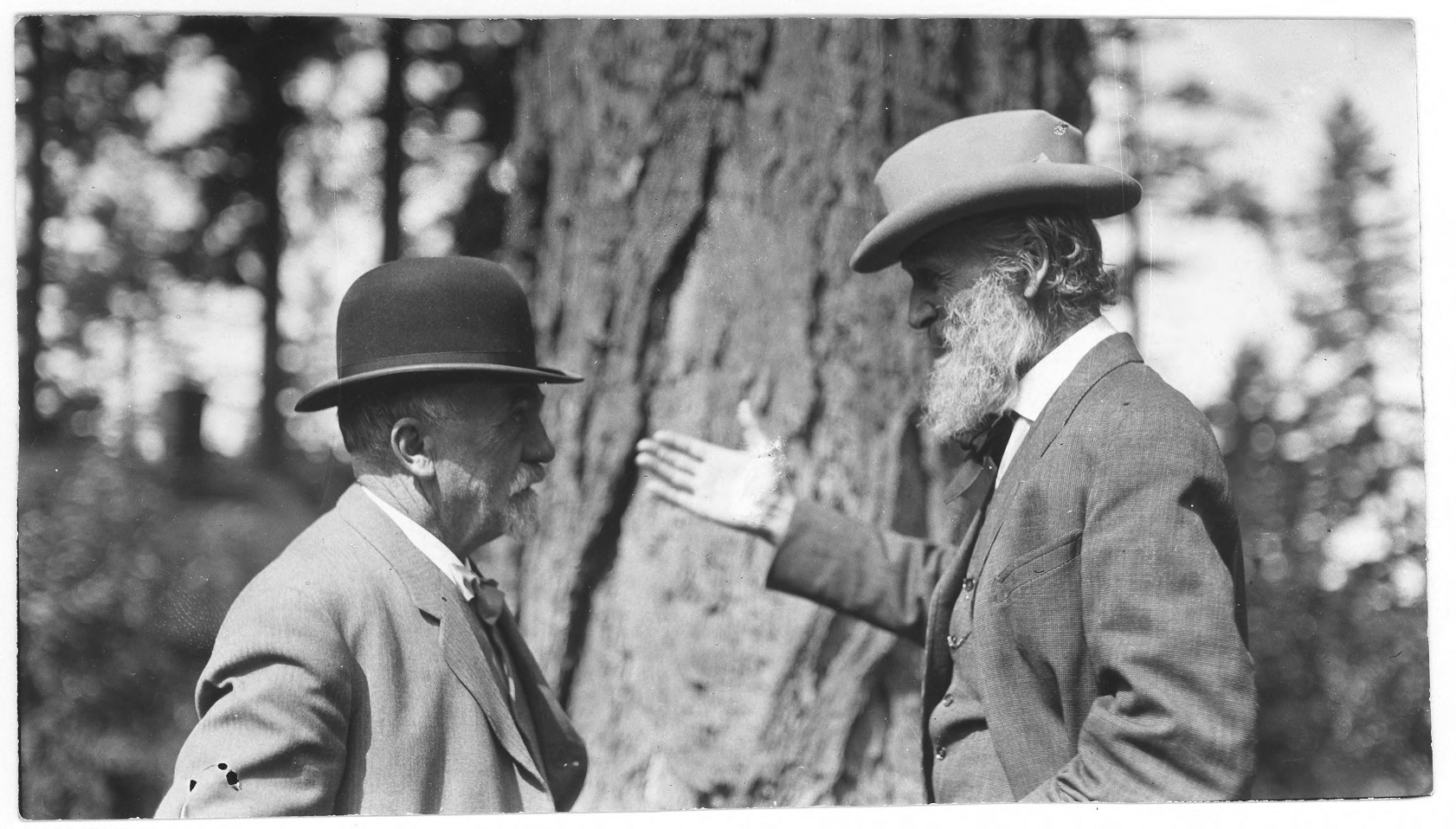

Muir with the horticulturist John McLaren, circa 1913.

University of the Pacific

Besides the interaction in Yosemite that you mentioned Muir had with Native Americans, what were some of his other interactions with them, and how did those change his views?

Most of John Muir’s knowledge about Native Americans came later in his life. He knew a few Indians in a remnant population in Yosemite Valley. But when Muir began taking longer trips up to Alaska, he met a lot of Natives, from the panhandle all the way up to the Bering Strait. There he saw the effects of white immigration and the diseases that came along, wiping out whole populations; the presence of alcohol and its effects; trade relations that were not good for the Indians. He wrote a diatribe against the white invasion. He said this is something the government should be up here doing: taking care of and protecting these people from being exploited, from being hurt and dying from all this.

There’s one episode from those days that really touched me, when Muir stopped at an Indian village somewhere and stayed overnight for several days with the people. Muir often hired them to take him on canoe expeditions up in these fjords. And in this village, there’s a little baby crying piteously. Nobody knows what to do. Its mother has died and the baby’s hungry. No one’s nursing it. So Muir goes to his canoe and he brings out a box of canned milk. He opens it and he spends the entire night with this baby, basically feeding it and holding it in his arms. He’s walking up and down, trying to soothe it. And the people of this village are so struck by it that they named the baby after John Muir. He gets word of this later on.

I think his attitudes toward Native Americans got more positive as he got to know more of them and particularly that came in Alaska. The population of Indians in California dramatically dropped even before he got there, due to gold mining and the Gold Rush. So he didn’t see many Native Americans there; he certainly didn’t see many whose lives had been what they were. The people he would see were alcoholic, whose lives were degraded from what they had been. Demanding whiskey, cigarettes, having little to do; their hunting was gone. In Alaska, he met a very different group of Native Americans who were undergoing invasion to some extent, but still were intact: their ways, their culture, their hunting, their economy, and their pride.

When he got to California, it wasn’t just the Indians who got him saying unflattering things. The white population, the people who were invading, the frontier types, the miners — he thought they were uncouth, savages, brutal, dirty, given over to alcohol. His writings are full of those descriptions. Nobody gets upset about that. You could, I suppose, claim that he was anti-working people generally, but that wouldn’t be true because he spent a couple of years in Indianapolis working in a factory. You can chase these sorts of things around and try to find something. But he certainly didn’t understand or know much about what we would call today systemic racism built into our institutions and cultures.

Muir, circa 1908.

University of the Pacific

You wrote that he had some radical ideas about justice — what were those?

I trace them back to poets like Robert Burns or people like William Wordsworth, English romantics, Scots. It was a kind of egalitarianism extended to the whole living world. This theme is very strong in his growing up, and particularly after he leaves home, when he goes to the South after the Civil War — where he has lots of encounters with African Americans, by the way. When he gets to California, he is writing constantly about the “other people of the planet.” He talks about the plant people, the bird people, the grasshopper people. He really takes it seriously, that all of these are organisms forming societies, and families, and relationships and they have a right to exist. There’s a point where on the trail up in Yosemite, he comes upon the carcass of a dead brown bear, just lying down the grass. And he sits down next to this carcass and writes on another little scrap of paper: “We live in an age of liberal principles.” He means that he also is a liberal, he is wide open to these ideas about human rights, equality. And goes on to say that we have allowed into our idea of heaven all kinds of other peoples in the world; we all can come into the Christian heaven, but “our liberal principles don’t extend to the bears, or other species.” So he’s going to sit down by the trail and mourn the passing of this brown bear.

I take this as meaning, “I’m a liberal, I’m an egalitarian; I believe in democracy, but my sympathies are not limited to just conventional ideas of humanity. We draw a line around ourselves, a fence around who we are as a species, and everybody is supposed to be equal, but everything outside of it’s nothing, absolutely nothing to us.” No, he says, “I don’t believe in that sense. And I’m going to talk about these liberal principles in a broader way.” And this, I think, is the moral value Muir thought he stood for, which didn’t exclude people but didn’t stop with people, that the Sierra Club ought to be talking about right now, ought to be remembering, and ought to be asking, “What can we do with it? And how do our programs encourage this or at least to examine it carefully and talk about it critically?”

Read Worster’s essay responding to the Sierra Club’s criticism of John Muir.

This article is from the California Sun, a newsletter that delivers must-read stories to your inbox each morning — for free. Sign up here.

Get your daily dose of the Golden State.