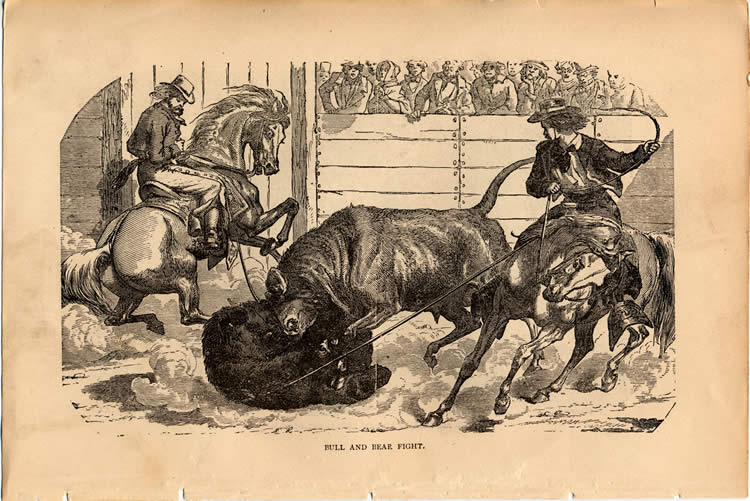

Depictions of bull and bear fights, in an 1890 edition of the Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, left, and in a 1911 edition of the San Francisco Call. Library of Congress; Bancroft Library

When California delighted in the bloodsport of bulls vs. bears

In the 19th century, California’s grizzly bears were commonly regarded as menaces. But settlers did see some value in the mighty beasts — as gladiatorial combatants.

Among the pastimes popular at the time were fights to the death between grizzly bears and bulls staged as Sunday entertainment for the after-church crowd.

“A bull and bear fight after the sabbath services was indeed a happy occasion,” the historian Hubert Howe Bancroft wrote in 1888. “It was a soul-refreshing sight to see the growling beasts of blood.”

An 1876 illustration of a California bear and bull fight that appeared in the British press.

(The Graphic)

The practice of setting animals against chained bears, known as bear-baiting, is as old as Rome. In medieval Europe, amphitheaters known as bear-gardens were built to host the events.

Introduced by the Spanish conquistadors, the bloodsport adopted a more homespun character in California. According to historical accounts, battles were waged in so-called “pits” or split-board arenas with raised platforms to provide a view for the women and children.

Men on horseback manned the perimeter with firearms lest any grizzly try to mount an escape.

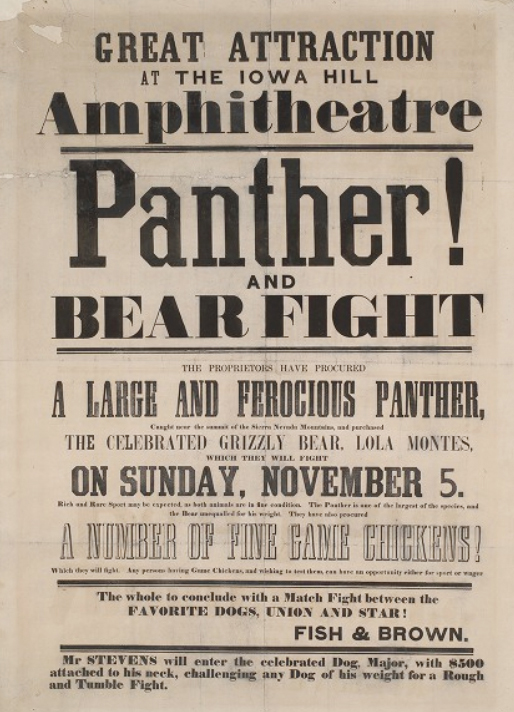

An undated 19th-century flyer advertised a fight between a panther and a bear in the Sierra foothills.

(Bancroft Library)

In a typical battle, the grizzly bear, standing up to eight feet tall and weighing as much as 800 pounds, would be chained to a post. The bull, its horns festooned with garlands, would be roped to the bear to keep the brutes in each others orbit.

Then, with the crowd in a frenzy, the burst of an officiator’s pistol would set off a melee of swiping, biting, and charging. More often than not, the bear emerged victorious.

Not everyone was comfortable with the cruelty of the contests. The German botanist Adelbert von Chamisso recounted watching a bear-baiting on the beach in San Francisco in 1816. “Unwilling and bound as the animals were, the spectacle had in it nothing great or praiseworthy,” he wrote. “One pitied only the poor beasts, who were so shamefully handled.”

The fights were still going strong mid-century when a wave of prospectors poured into California during the Gold Rush. Many of the newcomers found the spectacle disgusting.

In 1852, the Daily Alta California denounced the bull and bear fights held Sundays at the Mission Dolores as “a vestige of barbarism” and a “disgrace to the citizens of San Francisco.” Ordinances were passed limiting the fights in both San Francisco and Sacramento.

In time, the bloodsport faded along with the grizzly bear itself. Killed with abandon by the growing population of settlers, the burly symbol of California was scarce by the 1880s. It was extinct four decades later.

A drawing of a bull and bear fight that appeared in the Wide West in 1854.

(Bancroft Library)

California’s animal fighting legacy echoes to this day. Like the bear-baiting contests, cockfighting now thrives in a patchwork of makeshift arenas across the state.

Banned since 1905, the events are often held in secluded barns in farm country, where men drink beer and gamble as roosters weaponized with steroids and gaffs, or fighting blades, peck and claw each other to the death.

Just last year, sheriff’s deputies discovered more than 7,000 roosters being groomed for combat in a remote canyon outside Santa Clarita. It was largest cockfighting bust in U.S. history.

This article is from the California Sun, a newsletter that delivers California’s most compelling news to your inbox each morning — for free. Sign up here.

Get your daily dose of the Golden State.