Fiddletown's Chew Kee Herb Shop in an undated photo. (California State Library)

A gold rush, a wave of Chinese immigration, and an herb shop: the story of Fiddletown

When news of the gold discovery in California circled the world in 1848, no population beyond U.S. shores answered the call in greater numbers than the Chinese.

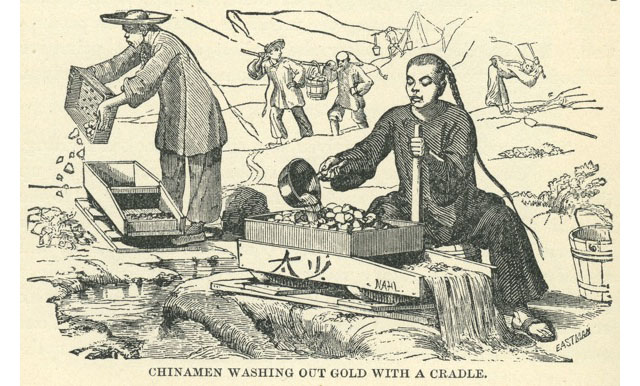

By 1860, migrants from China made up nearly a third of the state’s roughly 83,000 miners. After arduous journeys across the Pacific, often in flight from hunger or warfare, they arrived to the chaotic metropolis of San Francisco with visions of freedom and opportunity. Some prospered, acquiring legal claims in the Sierra foothills.

In the Aug. 15, 1857, edition of Jackson’s Weekly Ledger, a correspondent described an elaborate Chinese mining operation that spread nearly half a mile along the Mokelumne River. “I am informed that this year the river is pretty generally owned by Chinese,” he wrote.

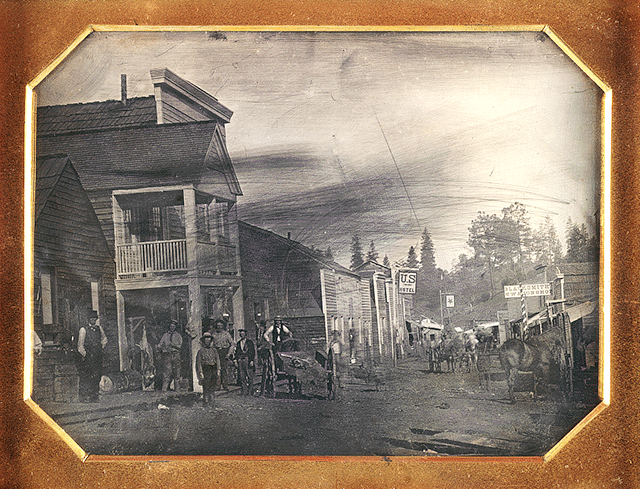

Chinese quarters sprung up in almost every Sierra community, one of which came to be known as a Chinese town. It was called Fiddletown, a hamlet along a tributary to the Mokelumne that was said to have been named for the fiddle-loving Missourians who lived there. Between the 1860s and 1880s, Chinese residents accounted for as much as half of Fiddletown’s population, which hovered around 1,000 souls, according to Elaine Zorbas’s local history “Banished & Embraced.” There was a gambling house, an opium den, and stores that sold Chinese food, clothes, and herbal medicines. The Lunar New Year was celebrated with cymbals, feasting, and firecrackers.

As the Chinese presence in California grew, however, so did the resentment of working-class white settlers who viewed them as competition for gold and jobs. Public officials organized boycotts of Chinese businesses and armed mobs drove Chinese miners off their claims. “The latest amusement,” the Ledger reported on Jan. 26, 1878, is “cutting off a Chinaman’s queue” — the distinctive braid of hair worn hanging from the back of the head.

Fiddletown became a refuge for Chinese migrants fleeing other Gold Country towns. But in time, it too was engulfed by a wave of xenophobia that had spread to the halls of Congress, which in 1882 barred all Chinese immigration. Two years later, arsonists torched Fiddletown’s Chinese section, leaving hundreds of people homeless. At the turn of the century, just 16 Chinese residents remained.

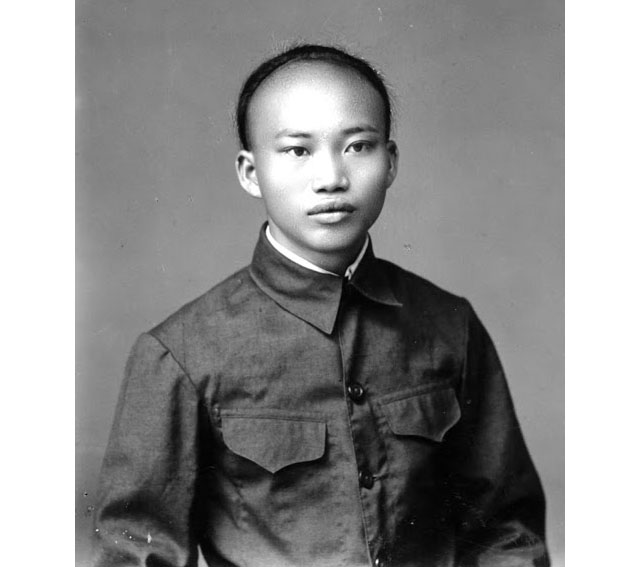

By the 1920s, there was just one: You Fong Chow, who went by Jimmie Chow, the caretaker of the old Chew Kee Herb Shop.

Chow was born in Fiddletown in 1885 to parents who returned to China, leaving the young boy in the custody of the local merchant Chew Kee.

Chow remained his entire life, working as a farm laborer, butcher, and handyman while sending money home to his family in China. According to oral histories included in “Banished,” Chow, a lifelong bachelor, was beloved by the townspeople, who extended regular invitations for dinner and holidays. “He was the most taken care of person you ever met,” Mary Lawrence, the wife of a friend of Chow’s, said in 1979.

When he suffered from arthritis in old age, neighbors cut wood for his stove and replaced his worn roof. Chow died of leukemia in 1965 at the age of 80 and became the only person of Chinese descent to be buried in the Fiddletown cemetery, breaking with the practice of returning remains to China to be buried with ancestors.

The Chew Kee Herb Shop, which Chow had inherited from Kee, became a state landmark. The rammed earth structure still stands, the centerpiece of what Fiddletown now regards as its proudest trait: its Chinese heritage.

This article is from the California Sun, a newsletter that delivers must-read stories to your inbox each morning . Sign up here.

Get your daily dose of the Golden State.