Much of Palm Springs sits on rented land. (Kamil Zelezik)

How a California tribe became one of the Coachella Valley’s most powerful forces

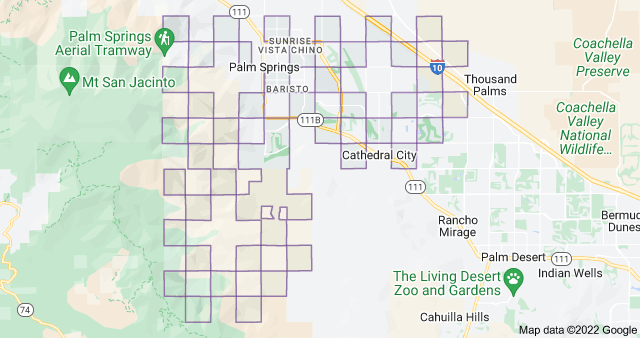

Search for “Agua Caliente tribal reservation” in Google Maps, and you’ll see a bizarre checkerboard design draped across Southern California’s Coachella Valley, pictured below.

It’s not an error. The borders of the Agua Caliente reservation emerged as a byproduct of America’s westward expansion in the 19th century and the technological innovation that facilitated it: the railroad. No longer would the settlement of Indian lands proceed slowly, the secretary of the interior, Jacob Dolson Cox, wrote in 1869, the year the transcontinental railroad was completed. “The very center of the desert has been pierced,” he said.

In many cases, the piercing of Native American territories was accomplished through land grants to the railroad companies. Rather than hand out ribbons of land along proposed routes, the federal government created grids of square parcels, giving away every other block while keeping the rest for itself with the hope that train service would raise the value of the land.

When the Southern Pacific Railroad arrived to the dusty Coachella Valley in the 1870s, the U.S. used part of its checkerboard share — nearly 50 square miles — to establish a reservation for the Agua Caliente, a tiny impoverished tribe whose ancestors had walked the valley since “time immemorial.” At the time, the remote land was deemed largely worthless. That was before the invention of Palm Springs.

As the desert became a fashionable resort destination in the early 1900s, restaurants and hotels popped up everywhere. A century later, roughly half of the glittering playground of Hollywood’s elite now sits atop land held by the Agua Caliente, whose members collect monthly lease payments from thousands of homeowners and businesses. The Agua Caliente, which also operates three major casinos, is today one of the Coachella Valley’s most powerful political forces and one of the country’s richest tribes.

In press reports, tribal members have sometimes bristled at questions about their wealth. But the late elder Vyola Ortner said she was proud of what the tribe achieved. “From my perspective,” she wrote in her 2011 memoir, “we did greater honor to our ancestors by prospering in the society that was forced upon us than by giving up or being taken in by self-righteous indignation.”

This article is from the California Sun, a newsletter that delivers must-read stories to your inbox each morning . Sign up here.

Get your daily dose of the Golden State.