A Sutro Baths postcard from 1907. The historic Cliff House is in the background.

How the Sutro Baths sparked a backlash against racism in California

The Sutro Baths, a glass palace of swimming pools to rival those of ancient Rome, opened in San Francisco on this week in 1896. The recreation center was dreamt up by Adolph Sutro, a silver mining magnate and San Francisco mayor who was inspired by the idea that the finer things in life should be available to all — up to a point.

Jim Crow-style racism was rampant in California at the time. So when a Black man named John Harris showed up to the baths for a swim on July Fourth, 1897, he was refused, an insult, he later told the S.F. Examiner, that left him feeling “disgraced and degraded.”

He brought suit under the Dibble Act, a brand new law that guaranteed Californians “of every color or race whatsoever” entry to places of public accommodation. He won. The jury set aside arguments by the Sutro family that Black patrons would offend the sensibilities of whites and awarded Harris $100 in damages.

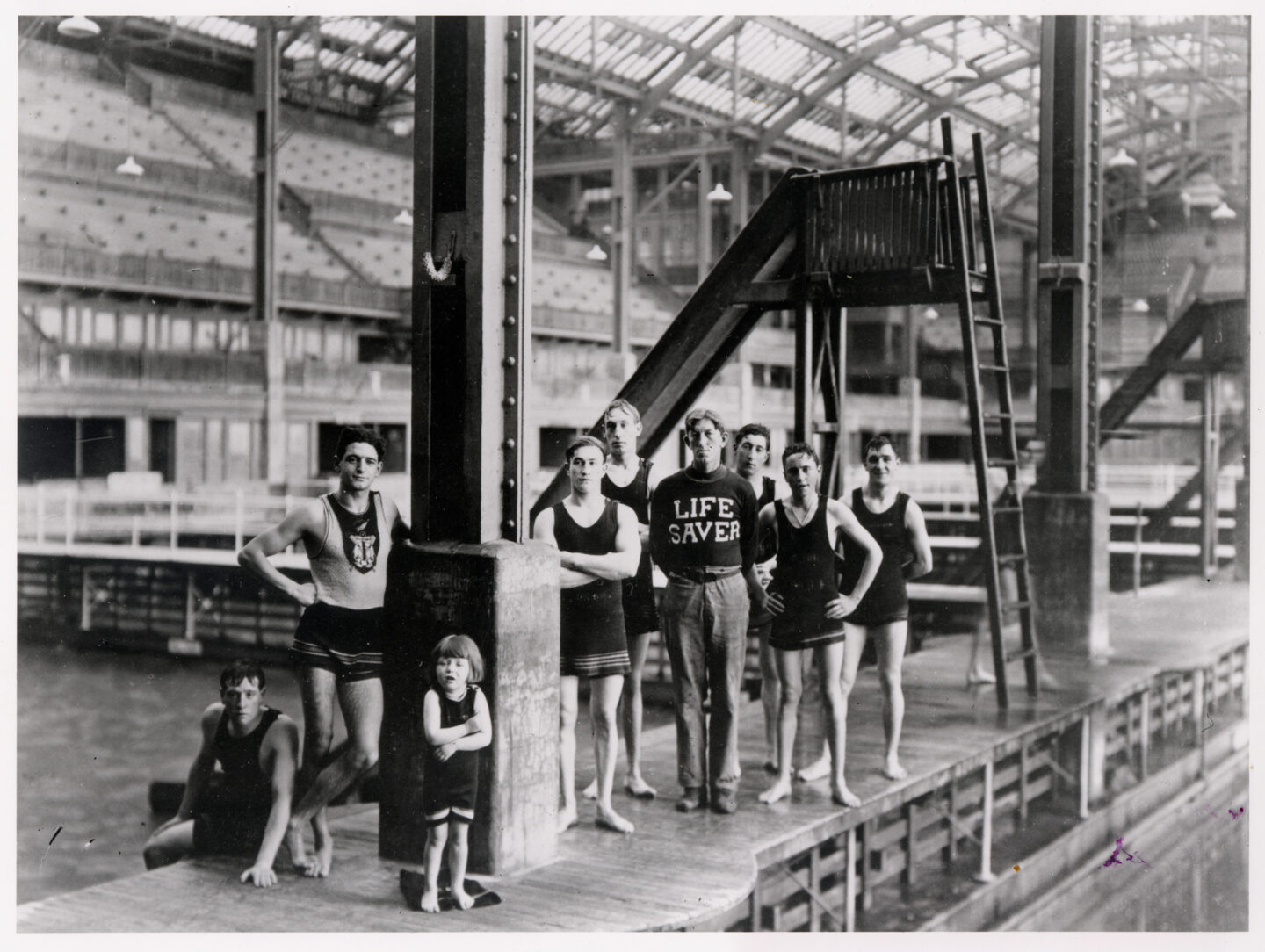

OpenSFHistory.org

The penalty was meager, but it proved that anti-bias legislation could prevail in the courts. Other lawsuits were filed challenging discrimination at an opera house in San Diego, a movie theater in Fresno, and a swimming pool in Riverside.

Little is known of John Harris, said Elaine Elinson, a civil rights historian. A voter registration card suggests he was in his 30s. He worked as a waiter. And he had the fortitude not only to challenge one of California’s most powerful families, but to invite the backlash of a racist society. The white press taunted him: “A negro is a negro and his color is his misfortune,” a newspaper in Santa Rosa wrote. The jury was so appalled that they asked the judge if they could simply ignore the law. (The answer was no.)

“He was definitely incredibly bold and courageous,” Elinson said of Harris.

Thomas Hawk/CC BY-NC 2.0

In 1959, the landmark Unruh Civil Rights Act was heralded as California’s first civil rights act, serving as a model for other states and the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964. But the legislation, Elinson said, was little more than a modification of the Dibble measure enacted more than 60 years prior and given teeth by Harris and others.

As for the Sutro Baths, it was little chastened by the court loss. John Martini, author of “Sutro’s Glass Palace,” said the photographic record suggests Blacks weren’t welcomed into the pools until the 1940s. In time, the complex fell into financial distress then burned to the ground in 1966. The stone and steel remains are now protected within a park along the northwestern edge of San Francisco, like the ruins of some vanished civilization. Open to all, it’s a popular place for reflection and a reminder of a not-so-ancient past.

● ●

Here are a couple collections of archival photos from the Sutro Baths. S.F. Chronicle | The Bold Italic

Get your daily dose of the Golden State.