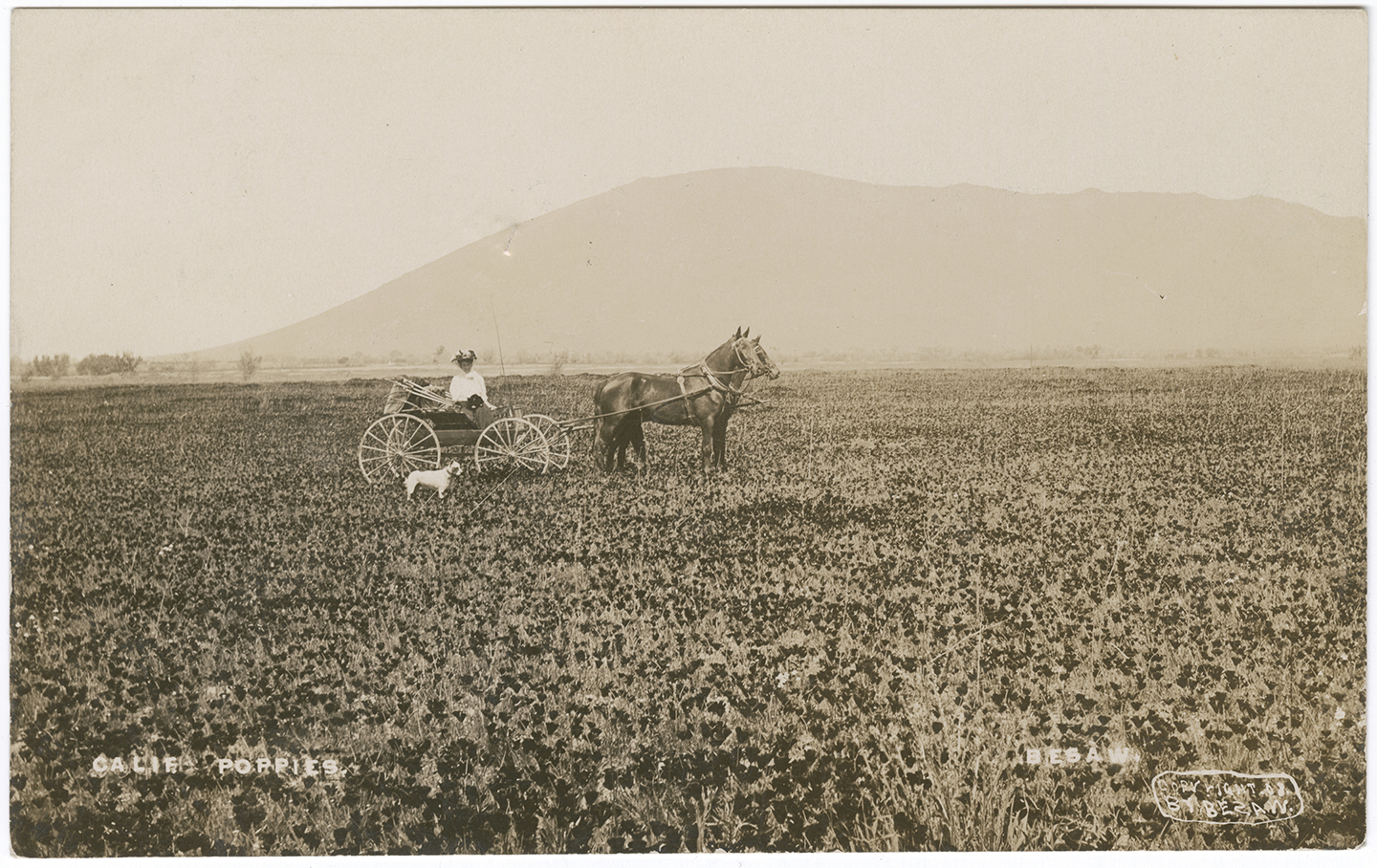

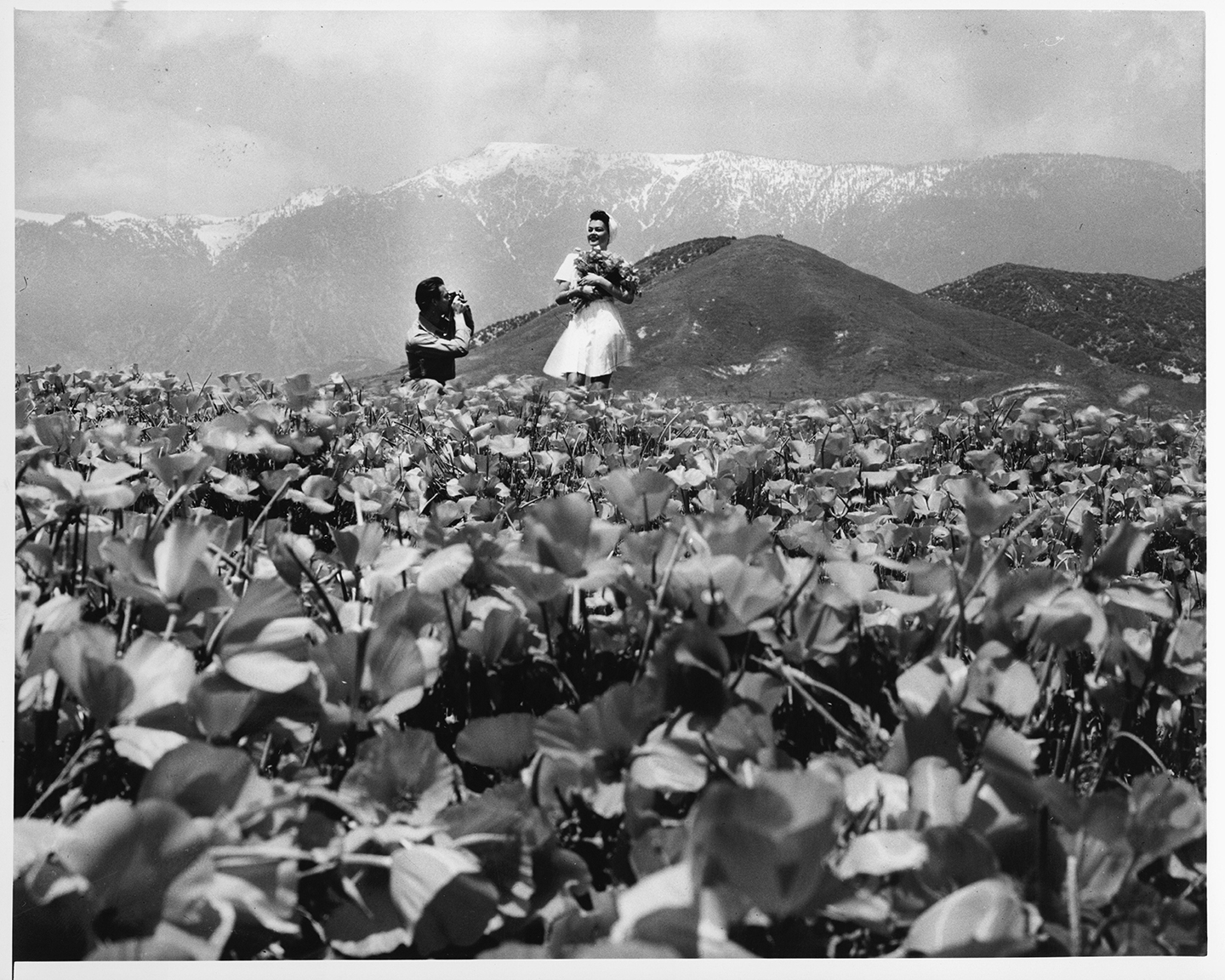

People picked poppies in Altadena in an undated photo. (Huntington Library)

In California, the wildflowers used to be everywhere

For most Californians, an outing to see the spring wildflowers involves driving an hour or two to preserves in the valleys, deserts, or foothills. But the flowers used to be everywhere. In 1847, the soldier Joseph Revere provided one of the earliest descriptions of the vast bloom within the Los Angeles basin:

“In the plain itself,” he wrote, “the richest and most brilliant wildflowers flourish in boundless profusion, and with a rank luxuriance which far transcends all the efforts of art. All colors, all shades of colors, all hues, all tints, all combinations are there to be seen.”

In 1876, Archduke Ludwig Salvator, visiting from Austria, wrote: “The fields in and about Los Angeles are particularly rich in flowers. Thus in March they appear to be cloaked in red; in April in blue; while in May they resemble passes of pure gold.”

And three years later, the botanist J.F. James observed: “Never have I seen such a brilliant mass of color. I have one patch in my mind now which, seen on a bright clear day, was, with the sun shining full upon it, too dazzling for the eye to gaze upon.”

Wildflowers became a centerpiece of Southern California culture, the ecologist Richard Minnich wrote in his 2008 book “California’s Fading Wildflowers.” Floral societies sprang up in every town, culminating in the first Rose Parade in 1890. The Mount Lowe Railway, opened north of Los Angeles in 1893, included a “Poppyfields Station” where passengers could get out and collect bouquets.

By the early 1900s, anxiety was mounting over the trampling of the wildflowers. “Spare the poppies,” a Riverside County newspaper warned in 1905. “If the crowds of people and children who are engaged in pulling up these beautiful flowers do not show more discretion, the poppies will not be there next year.”

More than a century later, the wildflower battles are still with us, only now they are being fought over ever-more distant fringes of nature, and some local officials are no longer asking visitors to behave. When Lake Elsinore’s mayor announced last week that the city was closing off access to its celebrated orange poppy hillsides, she brought along the county sheriff. Trespass, he warned, and you may find yourself in jail.

Below, a short gallery of California’s poppy tourists of yore.

Before it was taken over by suburban development, Altadena was a wildflower paradise. (Herald Examiner, via L.A. County Library)

This article is from the California Sun, a newsletter that delivers must-read stories to your inbox each morning . Sign up here.

Get your daily dose of the Golden State.