Teenagers outside Ouye’s Pharmacy in Sacramento’s Japantown, circa 1930s. (Harold N. Ouye family, via Google Arts & Culture)

Sacramento once had one of the nation’s most vibrant Japantowns

Sacramento’s old Japantown was born in the latter half of the 19th century, as migrants from Asia responded to California’s need for farm and railroad labor and later formed communities in depressed inner-city areas.

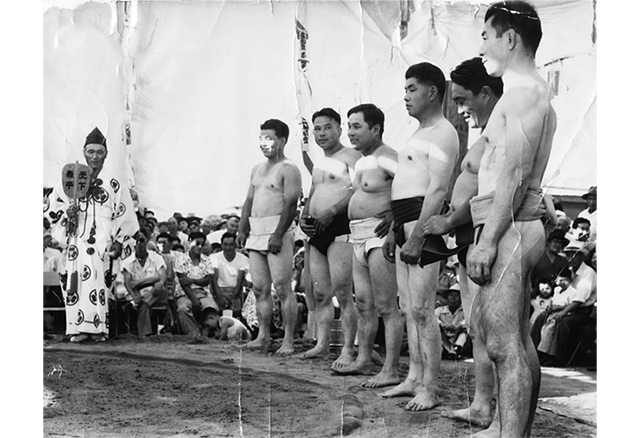

The Japanese diaspora opened shops that sold jewelry, fresh fish, 10-cent milkshakes, and other wares in a six-block area near the State Capitol. Colorful lanterns lit the street, where kids played hide-and-seek and musicians plucked the three-stringed shamisen late into the night. There were tea ceremonies, traditional dances, and sumo matches.

Then, on Dec. 7, 1941, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. Sensing the precariousness of the moment, Sacramento’s Japanese residents made ostentatious displays of devotion to the United States. They hung patriotic banners, delivered a statement of loyalty to Sacramento’s city manager, and bought an ad in the newspaper: “Yes, we are Americans,” it began.

It wasn’t enough. About two months after the attack, President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered the incarceration of all people of Japanese ancestry. By mid-May, Sacramento’s Japantown was deserted.

With the former residents behind barbed wire, the Sacramento City Council passed a resolution in 1943 opposing their return, citing “the treachery, faithlessness and untrustworthiness of the pagan Japanese.”

They returned anyway. Released after nearly three years of incarceration, the former residents got back to work, reinventing Japantown, now within a more ethnically diverse community of Portuguese, Mexican, Chinese, Korean, and African American residents. By the early 1950s, most of the professionals in the neighborhood were Japanese, including five dentists, four physicians, and three lawyers. A Japanese bowling league had 128 members. The festivals and sumo matches resumed.

But just as the neighborhood found its footing again, a new threat emerged. In 1954, city leaders who viewed Japantown as a blight on the downtown announced an urban renewal plan that they said would establish a modern gateway to the Capitol. It meant the total destruction of Japantown.

During City Council hearings, merchants and residents made impassioned appeals to the humanity of the city.

“We will not be able to withstand another evacuation,” testified Giichi Aoki, a music shop owner.

“What other people have had to take so much as the Japanese?” asked I. Sugiyama, a longtime resident.

The protests fell on deaf ears. In 1959, Gov. Edmund G. Brown Sr. pushed a shovel into the ground during the ceremonial groundbreaking. Once again, business owners had to liquidate their merchandise as they prepared to move. Within a decade, 15 square blocks were leveled, wiping Japantown off the map and scattering its former residents.

In its place rose office towers, a condo complex, and multiple bureaucratic buildings. Today, the only remaining Japantown structure, the old Nisei veterans post, stands as a poignant reminder of how disgraceful the anti-Japanese movement was. Now wedged between a parking garage and offices for the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration, it served as safe haven for Japanese-American soldiers who were excluded from veterans organizations after fighting for their country in World War II.

More from the California Sun

- California Sun readers share feedback on the newsletter

- Photos: Rare September snow dusts June Lake in Eastern Sierra

- Highway 1 used to be a wooden boardwalk for cars

- Swooning over San Francisco’s Tetris house

- The strange boundary line that divides California in two

Get must-read stories about California your inbox each morning . Sign up here.

Get your daily dose of the Golden State.