Traffic was shrouded by smog at Los Angeles International Airport in 1980. Lennox McLendon/A.P.

Photos: When L.A. smog was so bad people suspected a gas attack

Less than two years had passed since the attack on Pearl Harbor when a strange mist settled over Los Angeles.

People’s eyes and throats stung. The haze dimmed the sun, seeping everywhere like a “beast you couldn’t stab,” as one account put it. Panicked, some residents piled into cars and headed for the foothills.

In the confusion, a rumor spread: Maybe the Japanese had lobbed a sneak gas attack.

But it was no such thing. In July of 1943, Los Angeles had one of its first severe bouts with smog. Other events followed that summer, kicking off a blundering, decades-long effort to get Los Angeles’s air pollution under control.

A man strolled down Broadway in a gas mask in 1958.

Los Angeles Public Library

Climate and topography seemed to conspire against the booming city, by then America’s car capital. Mountain ranges surround the coastal plain, while a weather phenomenon known as temperature inversion acts like a lid pushing pollution to the ground.

The smog between the 1950s and ’70s got so bad that people would cover their mouths with handkerchiefs. Parents kept their children home from school, and athletes trained indoors. Newspaper articles called the air “choking,” “agonizing,” and “strangling.”

After automobiles were recognized as the primary culprit, California established the nation’s first tailpipe emissions standards in 1966. Innovations followed, crucial among them the introduction of antipollution catalytic converters.

U.C.L.A. scientists Richard D. Hopa, left, and Hiroshi Kimura demonstrated an experimental catalytic converter in 1960.

U.C.L.A. Library/L.A. Times Photographic Archive

Even as the number of cars on the road swelled, air pollution declined. Today, it’s less than half what it was in the 1970s. Even so, Los Angeles’s air remains among the dirtiest in the nation. A recent study estimated that each year more than 1,300 people’s lives are cut short across the region as a result of the poisons they breathe.

But the source of Los Angeles’s air pollution, it turns out, has increasingly belonged to another culprit: everyday products like deodorants, perfumes, and soaps.

A study published in the February issue of Science found that products made with petroleum-based chemicals now emit about as much air pollution in Los Angeles in the form of volatile organic compounds, or V.O.C.s, as vehicle tailpipes do.

Brian McDonald, a research chemist with the University of Colorado at Boulder and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the lead author of the study, said the findings came as a surprise. “Transportation is still an important source of air pollution,” he said, “but it’s not the only source of air pollution in L.A. anymore.”

This article is from the California Sun, a newsletter that delivers California’s most compelling news to your inbox each morning — for free. Sign up here.

A view of downtown Los Angeles from Arroyo Seco Parkway in 1948.

U.C.L.A. Library/L.A. Times Photographic Archive

Men inspected an experimental smog-control device on a smokestack in 1948.

U.C.L.A. Library/L.A. Times Photographic Archive

A view of the Civic Center in 1948.

U.C.L.A. Library/L.A. Times Photographic Archive

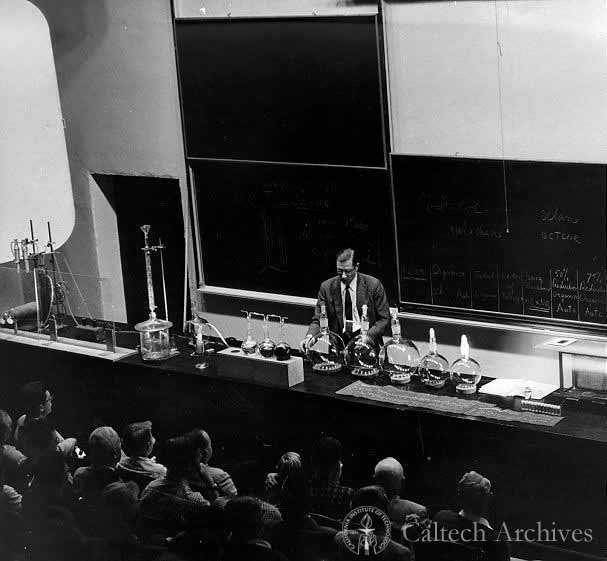

Arie Haagen-Smit delivered a lecture in an undated photo. The California Institute of Technology biochemist linked smog to automobiles, a discovery that sparked pushback from automakers.

Caltech Archives

Downtown Los Angeles in 1973.

U.C.L.A. Library/L.A. Times Photographic Archive

A smoggy Los Angeles street in 1960.

U.C.L.A. Library/L.A. Times Photographic Archive

Members of the Highland Park Optimist Club wore gas masks at a banquet, circa 1954.

U.C.L.A. Library/L.A. Daily News Negatives

Women fought through the smog in downtown Los Angeles in 1955.

Los Angeles Public Library

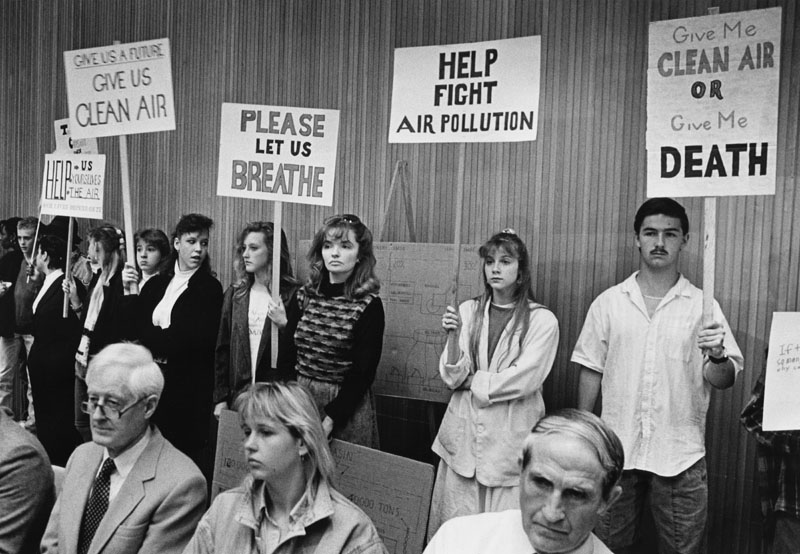

Protesters held signs during a meeting of the South Coast Air Quality Management District in 1989.

Los Angeles Public Library

A man at the entrance to his underground smog alert chamber in Manhattan Beach in 1971.

U.C.L.A. Library/L.A. Times Photographic Archive

A smoggy Los Angeles street in 1953.

U.C.L.A. Library/L.A. Daily News Negatives

Downtown Los Angeles in the summer of 2016. Air pollution has fallen sharply over the decades.

Richard Vogel/A.P.

Get your daily dose of the Golden State.