A Black miner in the northern Sierra foothills in 1852. (California State Library)

The complicated push to abolish slavery in California

When California added antislavery language to its constitution in 1849, it was motivated by greed as much as moral decency.

Weeks before the convention, a Texan named Thomas Green had shown up along the Yuba River to join the Gold Rush. With him were 15 slaves, whose names Green used to establish grandiose mining claims. Appalled, local whites called a meeting, and in July 1849 voted “that no slave or negro should own claims or even work in the mines.”

Days later, the Yuba River prospectors had the opportunity to send a delegate to Monterey, where the state’s first constitution was to be drafted. They chose William Shannon, a 27-year-old lawyer from Ireland who had witnessed slavery in Brazil and found it “loathsome” and “revolting.”

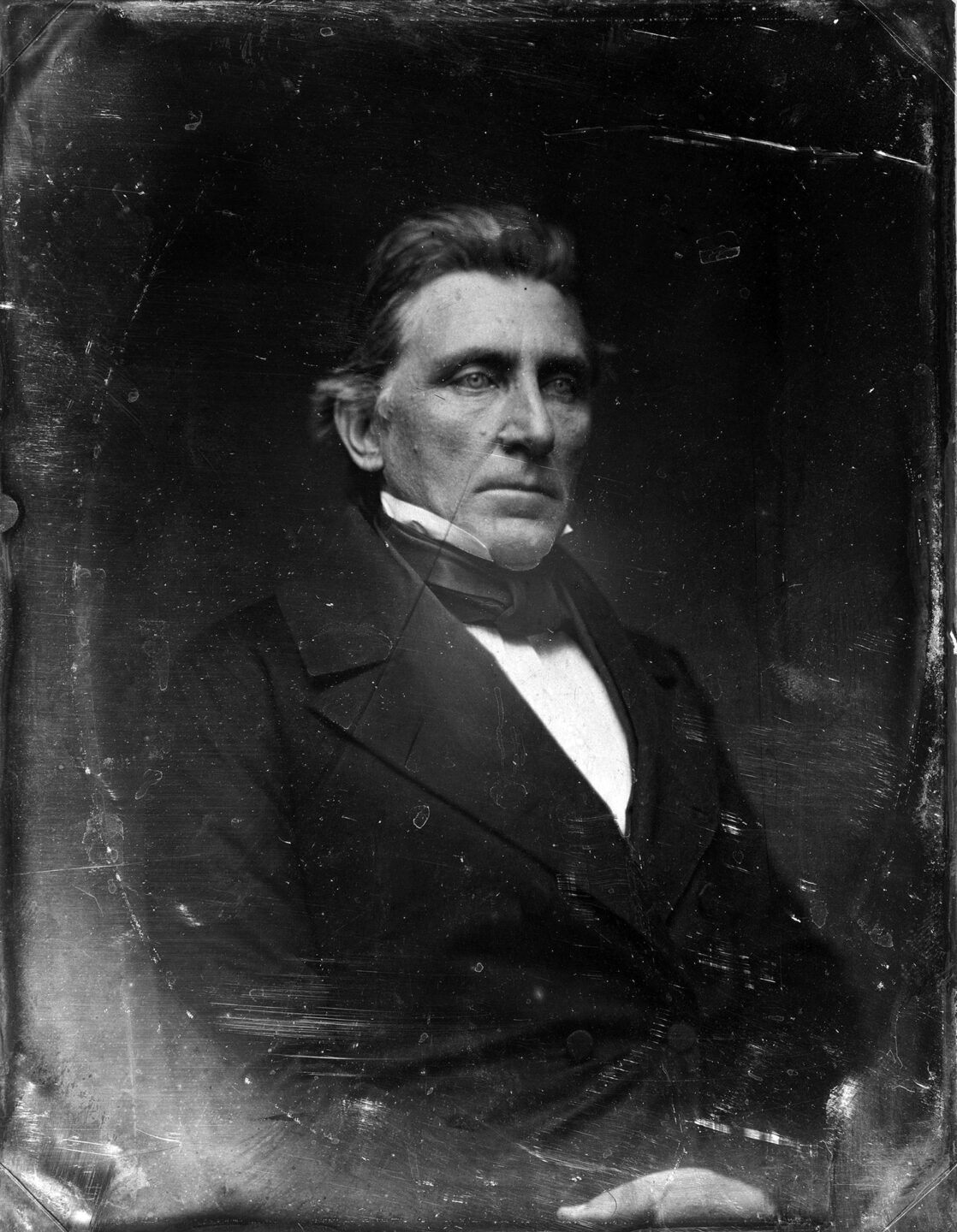

Library of Congress

It was Shannon who introduced a section to the charter prohibiting slavery. Seconding the motion was William Gwin, the owner of 200 Mississippi slaves. His support surprised some. But as the historian Leonard Richards recounts in his book “The California Gold Rush and the Coming of the Civil War,” Gwin understood the sentiments of the state’s forty-niners.

“In our mines are to be found men of the highest intelligence and respectability performing daily labor,” Gwin explained, “and they do not wish to see the slaves of some wealthy planter brought there and put in competition with their labor, side by side.”

Shannon’s motion was approved in a unanimous vote. Then for two full days the delegates hotly debated a proposal to bar even free Blacks from California. Again, a primary objective was to insulate white miners from competition. That motion was ultimately defeated, however, and the constitution was signed on Oct. 13.

Library of Congress

California’s antislavery stance jolted Washington, where the balance of power tilted further away from the Southern slave states. On Dec. 13, as members of the U.S. House debated the California question, Rep. Robert Toombs, of Georgia, took the floor. “In the presence of the living God,” he declared, if slaveholding is disallowed in California, “I am for disunion.”

Even so, California was formally accepted into the union as a free state in September of 1850. Tensions only worsened as disillusioned southerners agitated for the right to bring slavery into new western territories. A decade later, in a culmination of events that the historian Richards links in part back to those Yuba River miners, the Civil War began.

This article is from the California Sun, a newsletter that delivers must-read stories to your inbox each morning . Sign up here.

Get your daily dose of the Golden State.