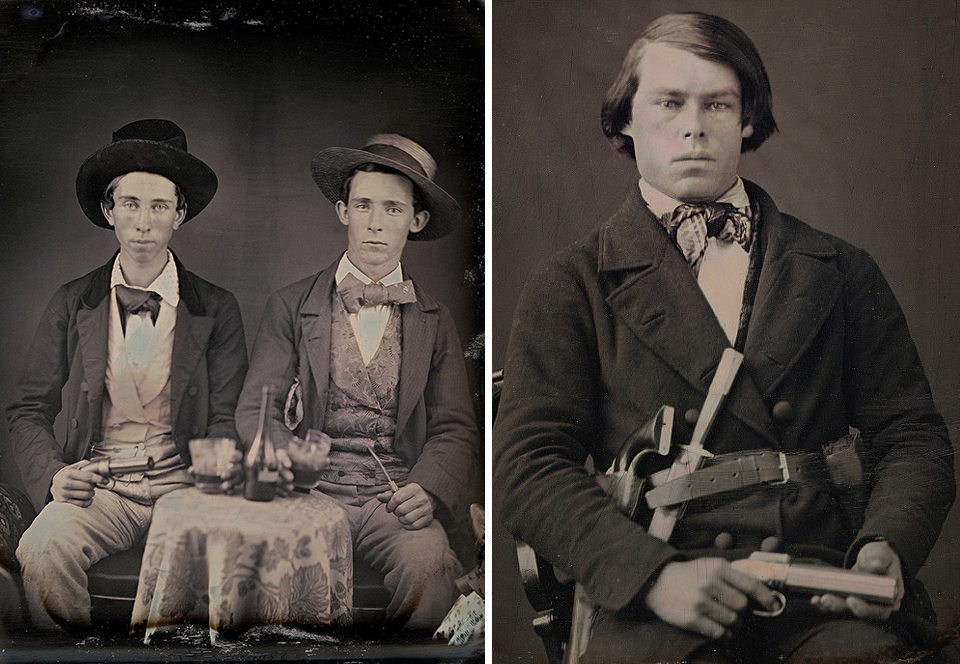

Miners in Plumas County, circa 1883. Widespread banditry made guns a part of the job. California State University, Chico

The man who fought 14 bandits and lived to tell the tale

The Gold Rush saw rates of homicide never equaled in American history. The reasons were myriad, among them feeble law enforcement, ethnic strife, and a bachelor cult of masculinity. Young men armed themselves to the teeth and died in brawls and raids by the thousands.

In December 1854 one of the bloodiest bursts of violence erupted. Jonathan Davis, a prospector, was trekking along the North Fork of the American River with two companions when 14 armed bandits pounced. In the days prior, the gang had robbed and killed 10 other miners in the area.

Both of Davis’ companions were quickly dispatched, one killed instantly and the other badly wounded. Davis, an Army veteran known for expert marksmanship, pulled out both of his Colt revolvers and fired methodically. Seven attackers fell dead or dying. Out of bullets, Davis produced a Bowie knife, slicing a nose and finger from one attacker and plunging the blade into another.

Canadian Photography Institute

By the end of the battle, 11 bandits were dead or close to it. Three others fled. Only Davis remained standing.

A coroner’s jury later summarized the affair, which had been witnessed by three miners on a nearby hilltop: “From all the evidence before us, Captain Davis and his party acted solely in self-defense, and were perfectly justifiable in killing these robbers. Too much praises cannot be bestowed upon them for having so gallantly stopped the wild career of these lawless ruffians.”

The story, repeated around campfires and in newspapers, passed into legend as the archetype of the Western gunslinger became a staple of literature and eventually film. Davis, who declared he only did what any man would, was said to disappear into the sunset.

This article is from the California Sun, a newsletter that delivers must-read stories to your inbox each morning . Sign up here.

Get your daily dose of the Golden State.