Men hung out at a Southern California saloon, circa 1898. Insult-driven brawls were common at the time. (Los Angeles Public Library)

The mob justice of 1850s Los Angeles

In 1850s Los Angeles, justice stood little chance.

Forged in violent conquest and riven by racial animus, the frontier city recorded a murder rate 50 times greater than that of New York City. Yet killers and thugs often escaped accountability as the city’s fledgling legal system was simply unable to keep up with the carnage. It was in this unsettled atmosphere that outlaw justice came to be viewed by even the most enlightened Angeleno as a public good.

Such was the sentiment in the fall of 1854 after Dave Brown, a former scalp hunter with a violent temper, fatally plunged a knife into his roommate’s chest during a drunken quarrel.

A crowd gathered and plotted revenge. Brown would surely have been doomed that day had the city’s mayor himself, Stephen Foster, not climbed atop a table and urged patience. If the courts fail to deliver justice, he declared, “I will resign my office and assist you in the hanging myself.”

It was three months later, in January 1855, that Foster kept his word.

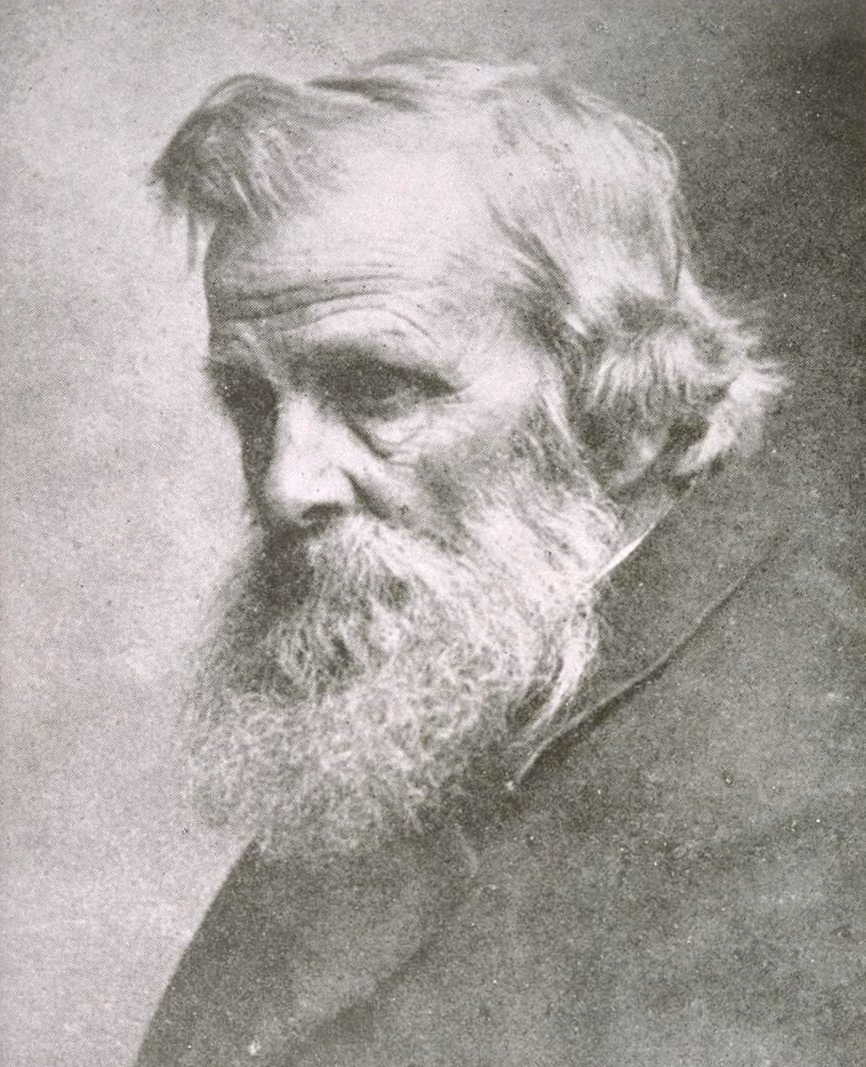

Bancroft Library/U.C. Berkeley

While a local jury returned a guilty verdict against Brown, California’s Supreme Court issued a stay of execution. On Jan. 12, 1855, Foster informed a gathering at the jailhouse that he had resigned as mayor and asked what they wanted done with Brown. “Hang him!” was the reply.

So be it, said Foster, who anticipated a violent clash with the sheriff and his deputies. He added, “And I will die with all of you.” Armed with axes, men forced their way into the jail to find that the lawmen had fled. Brown was dragged from his cell and hanged from an improvised gallows across the street.

Two years prior to the lynching, in 1853, the Los Angeles Star had described Southern California this way: “There is no country where nature is more lavish of her exuberant fullness; and yet, with all our natural beauties and advantages, there is no country where human life is of so little account.”

Yet Foster’s embrace of mob violence was seen by the public as the righteous act of a leader with no better choice. Popular justice, they reasoned, was better than no justice. Less than two weeks after Brown breathed his last, Foster was reelected as mayor in a near unanimous vote. The city marshal who opposed the vigilantes was forced to resign.

This article is from the California Sun, a newsletter that delivers must-read stories to your inbox each morning . Sign up here.

Get your daily dose of the Golden State.